Five Overlooked British Policies that Led to the American Revolution

You've heard of the Townshend Act, the Boston Massacre, and the shot heard around the world, but do you know the impact that Molasses, the West Indies, and British currency had on Americans?

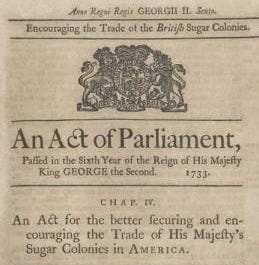

The Molasses Act of 1733

The British West Indies in the Caribbean had become an essential agricultural asset for the British Empire since it was first captured in 1623. The islands were supposed to be the main source of Molasses for the American Colonies, but due to foreign competition in the market being cheaper, the Colonists opted to trade less with the British.

In response to the lack of trade as well as news that American Colonists were attempting to produce Molasses in North America, the British enacted a tax on foreign goods in the Molasses Act of 1733. The full list of taxed items included Molasses, Rum, and Sugar. Parliament had debated the topic of controlling the Molasses trade for years, arguments ranged from freezing the trade altogether to simply taxing it.

In the early 1730s, arguments over a trade tax for North America were hotly debated in Parliament, with British merchants and West Indies farmers complaining over the fact that the American Colonies were engaging in economic trade far more with French merchants than British ones.

The first concept of the bill came in 1731, when Parliament, at the urging of Sugar Plantation farmers in the West Indies, attempted to pass an act titled “An Act for the better Securing and Encouraging the Trade of his Majesty’s Sugar Colonies in America.”

The act was planned to stop American trade with other foreign countries. Considered too harsh by the House of Lords in Parliament, it was quickly vetoed. In 1732, the farmers and Parliament supporters strived to pass a similar bill, but it was ultimately vetoed by the House of Lords due to the controversy over freezing American trade.

Changing their strategy, the farmers and their political supporters pushed a new bill in 1733 that would not stop the economic activity, but rather tax it. The strategy worked with the bill passed, stating clearly: “There shall be raised, levied, collected and paid and upon all molasses or syrups of such foreign produce or manufacture . . . the sum of sixpence of like money for every gallon thereof.”

The Molasses Act of 1733 would later be a stepping stone and overshadowed by the better-known Sugar Act of 1764, which was the revised version of the former. Between the two periods, smuggling of Molasses and other goods ran rampant in the Colonies, as Colonists’ businesses were hurt by the taxes on the goods.

To the Ministry of George Grenville in Great Britain’s government, the ignorance of the 1733 policy became a reason to issue the Sugar Act of 1764. Both acts together would be seen by the Colonists as the British waging war against the economy of the Middle Colonies.

The British, in enforcing such an act, would not realize that they had manufactured one of the many sources for a future rebellion among the 13 Colonies. "I know not why we should blush to confess that molasses was an essential ingredient in American independence,” wrote John Adams to William Tutor in 1818.

The Unofficial Policy of Saltatory Neglect (1740s)

Throughout the 1740s, the British government of Robert Walpole pivoted from earlier policies of strict Colony regulation and started to overlook the colonists’ trade with other empires such as France and the Dutch. Merchants in New England, for example, were enriched by trade with the French, allowing them to then buy more goods from the Mother Country (Great Britain).

British Officials, as well as Walpole himself, ignored the trade between the Colonies and Britain’s rival France with the belief that a relaxation of trade regulations would be beneficial for Britain’s economy in the long run.

Similar to the Molasses Act of 1733, though, the relaxation on trade allowed the 13 Colonies to enrich themselves and directly contributed to their realization that the British Empire and the American Colonies were going down different paths.

The economic system of Colonial America had grown in strength as time went on, making it an annoyance for the British Empire to later demand the Colonists pay the debt of the French and Indian War in the 1760s.

The Currency Act of 1751

Since the mid-17th Century, the Colonies began issuing new bills of credit in response to the British refusing to enact a British currency that could carry weight in North America. The Colonies had been losing their supply of British coins in North America after trading them with Great Britain due to high import costs. New England Colonies such as New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut had resorted to creating a new currency to keep business flowing.

By 1751, the separate currencies set up by these Colonies had struggled in value when compared to other countries’ currencies, being depreciated significantly. In response to the economic pain, the British government attempted to freeze the different currencies and establish only one money system in the New England Colonies with the Currency Act of 1751. But this act would prove to be given too late.

The act described the situation by stating: “debts have been discharged with a much less value than was contracted for,” resulting in “confusion in dealings, and lessening credit in the said colonies or plantations,” that had ultimately been “to the great discouragement and prejudice of the trade and commerce of his Majesty's subjects.” The act also called for the firing of Colonial Governors who refused to obey the new rules.

The Currency Act of 1751 did not have strong resistance when the news reached the Colonies. But in 1764, the British Government under Lord North and King George III would extend the 1751 ban on currency to the middle and southern colonies, similar to the extension of other acts like the Molasses Act of 1733.

The reaction was not intense, but it squashed the Colonists’ hope of a stronger independent economy in the near future. A Quaker Merchant in Pennsylvania, Isaac Pemberton, wrote that the act had brought “clamor” and “uneasiness” among the Colony. A New York Merchant and General Assembly member, John Watts, wrote that the Currency Act’s extension would “take away what little Energy it (Paper Money) has.”

It was a small step to sustain the economy, but it accidentally became one of the many reasons for the Colonists to openly rebel against the British in the 1770s.

The Military Legislation of 1763

In 1763, the British government passed legislation in Parliament to keep a large number of soldiers in North America, believing the Colonists would be perfectly fine paying the cost of keeping the soldiers. Like the acts before, they did not foresee its unintended consequences.

The new ministry of John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, and King George III ran an Empire that had accumulated a massive debt of 122 million pounds from the French and Indian War in North America. Since the soldiers were stationed across the Atlantic, John Stuart and King George believed there would be no issue with the American Colonies paying for the cost.

The origins of the legislation are given new light through Bute Ministry’s Private Secretary Charles Jenkin and his report of the House of Commons debate in 1763 between Secretary of War Welborn Ellis and Lord Mayor of London William Beckford. According to the report, Ellis argued that a large force of British soldiers in America was necessary due to the French “keeping a great force in their islands.”

He proposed that “the American force was intended to be paid for a future year by America,” hoping, as noted by Historian Peter Thomas, that the act of having America pay for the soldiers would not make it seem as if the Crown was asserting unnecessary influence over the Colonies.

William Beckford argued for a decrease in the number of soldiers stationed among the Colonies, adding that France was actively diminishing their military presence, but agreed with Ellis that “America can pay an army but that no inducement to keep one there. The money may be transmitted to England and applied to uses here.”

The legislation was ultimately passed, increasing the presence of British Officers and their Regulars across the North American Colonies, with both sides of the debate missing the negative impact of having the Americans pay for the additional troops and stationing them there without the Colonies’ say.

The Massachusetts Government Act of 1774

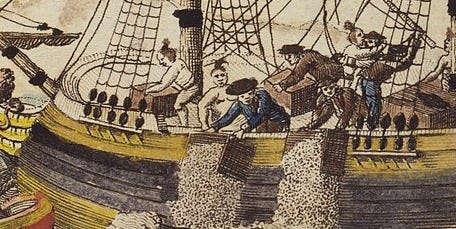

“But, BEHOLD what followed! A number of brave and resolute men, determined to do all in their power to save their country from the ruin which their enemies had plotted…emptied every chest of tea on board the three ships commanded by captains Hall, Bruce, and Coffin, amounting to 342 chests, into the sea ! !” declared the Boston Gazette on December 20th, 1773.

The infamous Boston Tea Party had occurred, and the British Government, shocked by such a reaction to their tax on tea, issued the Intolerable Acts against the Colony of Massachusetts, where the British goods had been destroyed.

One of the intolerable acts, the Massachusetts Royal Colony Act (or Massachusetts Government Act), would drastically alter the Colony’s government structure by having officials appointed by the Colonists now be chosen by the Royal (British) governor.

On the appointment of the Sheriff, Chief Justices and Judges in the Colony, the Royal governor now had “full power and authority to nominate and appoint the persons to succeed to the said offices; who shall hold their commissions during the pleasure of his Majesty,” notably, “without the consent of the council.”

To the Massachusetts Colonists, this affront against their Colony was in direct violation of their 1691 charter that had given them the right to be self-governed. The Colony reacted by establishing the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts, where they would publicly denounce the Act in their very first meeting in Salem on October 7th, 1774, calling it “unconstitutional, unjust, and disrespectful to the province,” and asserting that it was “further proof, not only of his excellency's disaffection towards the province, but of the necessity of its most vigorous and immediate exertions for preserving the freedom and constitution thereof.” Other Colonies across North America were establishing new governments in reaction to the British attack on Massachusetts’ Charter.

Every source used for the research of this article is embedded within. Click on the highlighted words to reach the source I used for its paragraph.